Featured Reader

Virtual Event on June 10th, 2025–6:00 P.M to 8:00 P.M.

Live stream will be available on our YouTube Channel at the time of the event!

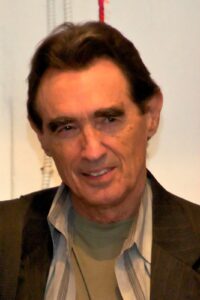

Clive Matson

Clive Matson (MFA Columbia University 1989) grew up on an avocado ranch in Southern California and writes from an itch in his body and that’s “old hat,” asserts his tutorial Let the Crazy Child Write! (1998). Beat Generation writers Herb Huncke, Michael McClure, Diane di Prima, John Wieners and Alden van Buskirk were his teachers in New York in the 1960s and he immersed himself in the deep passions that run through us all. He taught creative writing at U.C. Berkeley Extension for a dozen years and now, after finishing Hello, Paradise. Paradise, Goodbye (New Generation Beat Publications 2025), he offers online classes and supports students on Wordswelljournal.org. More at Instinct, Be My Guide (Interlitq, 2022). Clive is the recipient of the Berkeley Lifetime Achievement in Poetry Award in 2012, was named the Best East Bay Writing Teacher in 2006 and received a PEN Oakland Josephine Miles National Award in 2003.

To learn more, visit https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clive_Matson and http://matsonpoet.com/.